Educating the majority of the populace about the real experiences of minorities is an issue that is gaining currency in our time in view of the numerous nauseating high-profile cases of police brutality against unarmed blacks, black church burnings throughout the south, racist attitudes on the lips of viable presidential candidates, and also, on the positive side, the rise of writers such as Marlon James, winner of the 2015 Man Booker Award, and Ta-Nahisi Coates, journalist, writer, and activist.

Educating the majority of the populace about the real experiences of minorities is an issue that is gaining currency in our time in view of the numerous nauseating high-profile cases of police brutality against unarmed blacks, black church burnings throughout the south, racist attitudes on the lips of viable presidential candidates, and also, on the positive side, the rise of writers such as Marlon James, winner of the 2015 Man Booker Award, and Ta-Nahisi Coates, journalist, writer, and activist.

I personally need such education and have been seeking to know and understand the everyday lives of those who do not experience the privilege I have simply because of skin color.

But as they say, be careful what you ask for, or at least be prepared for the story to be more devastating than you expected.

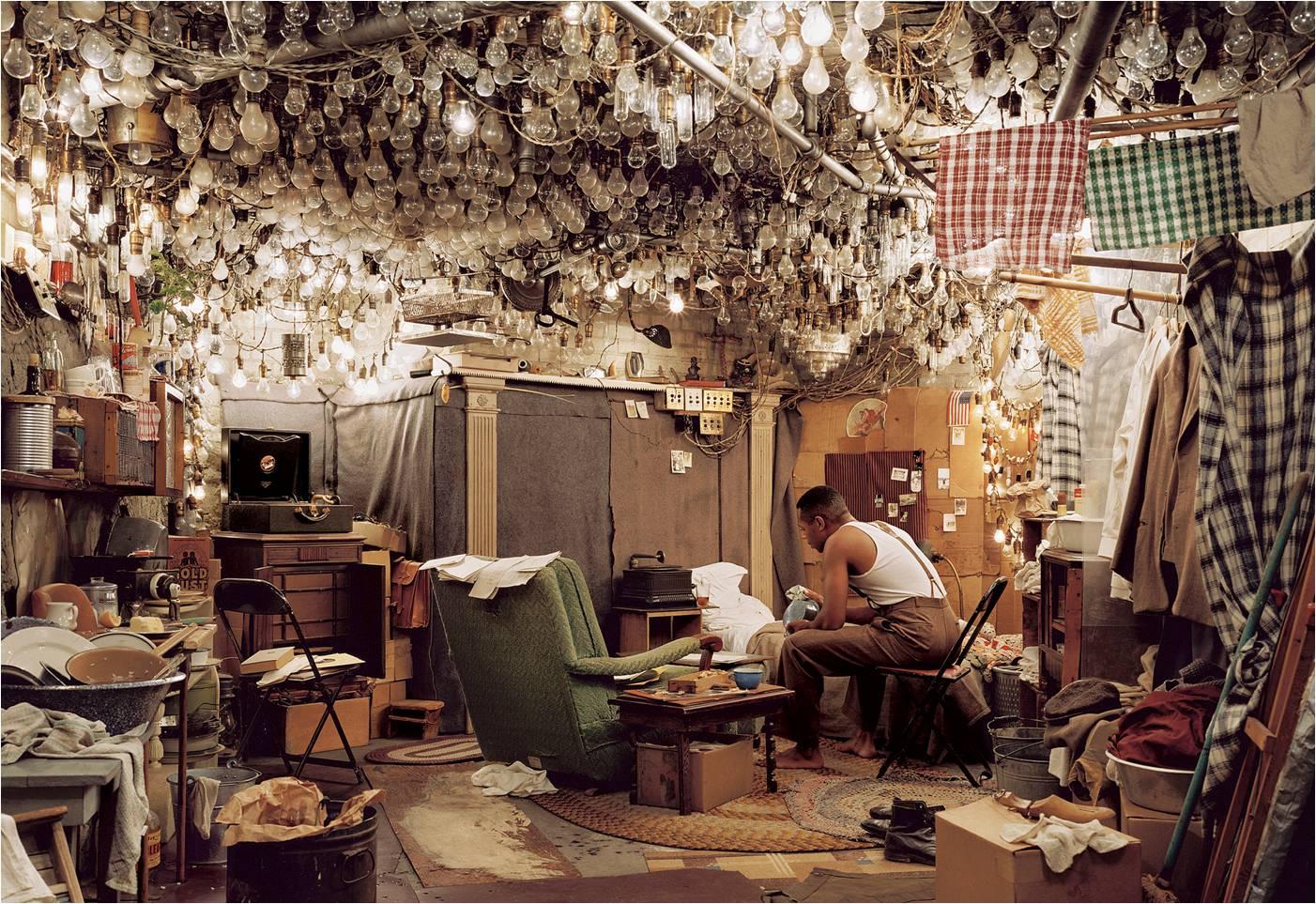

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man opens with what may be one of the most harrowing and memorable sequences ever put to paper: our nameless hero, beaming with pride and purpose, is to give the commencement speech at his school. But before the “ceremony” he is rounded up with other black men and forced to participate in a Battle Royal for the enjoyment of the white administrators. Summary here cannot do it justice. The abuse and mockery and degradation of the black men in the scene was unlike anything I’ve ever read.

The book goes on to describe his eye-opening experiences at college, his unjust expulsion from the institution, and the months immediately following, again, all scenes that leave the reader gasping for breath unable to put the book down.

The remainder of the book describes his residence in Harlem, his appropriation by the Communist Party, and many subsequent encounters and upheavals.

It was pointed out early, immediately following Jordan’s opening essay, that a major theme of the book was identity: we never know the protagonist’s name, he is mistaken for Reinhart, he is “invisible”. The brotherhood even gives him a new identity.

Noah very helpfully pointed out that southern racism, at least within the 1952 context of the book but certainly ongoing today, is very apparent and obvious. It is seen in language, in laws of segregation, prejudice, inability to get justice or protection from the magistrate, in the poverty and marginalization of black people in general. Northern racism, on the other hand, as portrayed in this book, is more insidious—denying race, denying identity, and suppressing awareness of the centuries-long oppressive black experience which is largely invisible and not understood by whites.

But I cannot finish this entry without hailing the exquisite style and sheer writing brilliance of Ellison that comes out in this book. A fan of symbolism, I personally enjoyed how rich and ubiquitous were his use of clues, cyphers, and symbols. The flow of his narrative was all his own, extremely creative and strikingly original in many sections. What a shot in the arm this book was!

For November the book is Ragtime by E.L. Doctorow.

For December, the winners of the vote were noir two-fer of The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett and The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler.