December was the month in which the Austin Athenaeum read two books from the noir genre: The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, a divergence from our normally more heady fare, but an opportunity to branch out into new territory however so low-brow.

December was the month in which the Austin Athenaeum read two books from the noir genre: The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, a divergence from our normally more heady fare, but an opportunity to branch out into new territory however so low-brow.

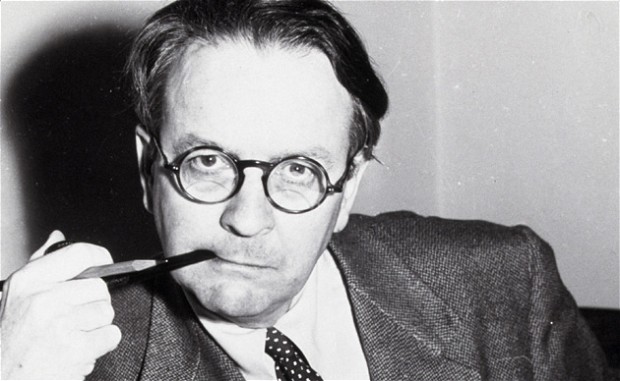

On the one hand, Philip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (a street euphemism for death), the former cop who didn’t play by the rules and had to become a private detective. He chases down multiple threads, dodges bullets and dames, tells law enforcement where to get off, and in the end reveals just about every other character in the book to be a shyster.

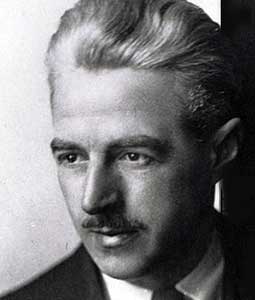

On the other hand, Sam Spade, detective of Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, the slightly more gentlemanly shamus who blows up the whole intrigue over the bogus statue and sends the greedy artifact collectors back to the Middle East to find their quarry.

In our lively discussion it was noted that Flannery O’Connor was famously harshly critical of the noir genre. No question that the 1950’s sensibilities and manners of the books are howlingly sexist and un-PC by today’s standards. The provenance of the books was alcohol-fueled and tinged by Hollywood bouncing gleefully nearby waiting to turn the books into movies.

Some interesting aspects were brought out. The sheer Americanism of the heroes, for example. The noir genre seems largely borrowed from the British gentry such as Father Brown and Sherlock Holmes, and coupled with the pent-up cynicism toward institutions that bloomed in the United States following World War I. It was then taken into an alley, forced to drink bourbon, and pistol-whipped into something fiercely individual, jaded, disillusioned, and cynical, just the ticket for American audiences.

Some interesting aspects were brought out. The sheer Americanism of the heroes, for example. The noir genre seems largely borrowed from the British gentry such as Father Brown and Sherlock Holmes, and coupled with the pent-up cynicism toward institutions that bloomed in the United States following World War I. It was then taken into an alley, forced to drink bourbon, and pistol-whipped into something fiercely individual, jaded, disillusioned, and cynical, just the ticket for American audiences.

In the United States, law enforcement isn’t enough. It’s too corrupt. It’s like it’s all a game, see, you have to go outside the system, see, if you wanna get things done and get to the bottom you gotta break some rules, crack some skulls, smack some yeggs around, see.

Finally, two interesting features in Maltese Falcon were discussed at length. First, the parable of “Charles Pearce”, the guy who is almost killed by a falling beam and is stirred thereby to change his life view from one of personal control of one’s own destiny to one of surrender to the randomness of fate. The real life Pearce was a philosopher who emphasized the importance of randomness in nature, and the parable seemed a clever commentary on Sam Spade himself.

The second feature was the uncanny similarities between Wilmer Cook, Casper Gutman’s punk hitman, and Rhea Gutman, Casper’s daughter who appears is only one scene drugged and barely conscious. Could these be the same person? The evidence grew as we considered it: his feminine features, his relating to Gutman as a father, his resistance to looking directly at Spade. Why would Hammett do that? It was odd. It didn’t seem to advance the story, and Rhea was the most minor of characters.

The final opinion of the group toward the books was both general enjoyment but a sense that it is not a genre that we would return to. Compared to the wealth of reward we generally receive from our selections, these two had less to offer beyond an atavistic imagination informed almost unavoidably by Humphrey Bogart.

The book for February was voted to be The Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer.