In September our book was William Golding’s iconic Lord of the Flies. Iconic, but not classic, so said some at our table. Which is not to say it’s themes are not timeless. The book’s merit of the word “classic” however seems to be up for debate.

In September our book was William Golding’s iconic Lord of the Flies. Iconic, but not classic, so said some at our table. Which is not to say it’s themes are not timeless. The book’s merit of the word “classic” however seems to be up for debate.

But I’m getting off too early into the weeds. LOTF was early acknowledged to be a book full of symbolism, stopping short of becoming all-out allegory.

Symbols that required analysis include the conch, the beast, the realm of the adults, the beachfront area, the sea, the pig’s head, the dead parachuter, Piggy’s glasses, Piggy himself, Ralph, Simon, and Jack.

A basic high school familiarity with the book says that it is a portrait or microcosm of humanity where the rule of law is removed. Golding suggests that we are all children who have the propensity to return to savagery if we were in a similar situation as the children.

What generated debate was the question of how the presence of various influences might mitigate our decline into abject barbarism. Would not adults be more industrious and organized if stranded on a desert island? How did mankind arise from a primitive state to the current level of civilization anyway (read Guns, Germs, and Steel for a substantial answer to that question)? Isn’t there more to human flourishing than the rule of law, namely, the common grace of God?

Another observation was the inescapable religious symbolism throughout, probably attributable to Golding’s education as a classicist and his British cultural identity most likely steeped in Church of England, Judeo-Christian mores and metanarratives. The island, clearly, is the realm of mankind. The realm of the adults, in this writer’s estimation, is something like the realm of the divine — the source of order, law, judgement, and indirectly all of the civilizing influences those institutions bring.

The boys’ descent into savagery, resulting in the murder of two already and moments away from the murder of Ralph, stopped in its tracks by the appearance of the adult officer (uniformed, civilized, and bearing a sidearm). The return of “the adults” to “rescue” them was the prime longing at the start, but steadily faded from view until even noble Ralph seemed to be forgetting their purpose in keeping the fire lit.

The appearance of the officer, given an Anglican worldview, looks strikingly like Judgement Day, when the bloody savagery of humans is suddenly dispelled by the vision, and remorse for his crimes are now the obvious matter to be dealt with.

The symbol of the pig’s head, which for Simon becomes the Beast incarnate, is another pagan/Satanic, idolatrous image, suited to primitive totemistic religion.

Much more could be said about LOTF and about Golding himself, and about the place of the book in the western canon. All agreed that the book was important and valuable, and we were glad to have a chance as adults to reread it.

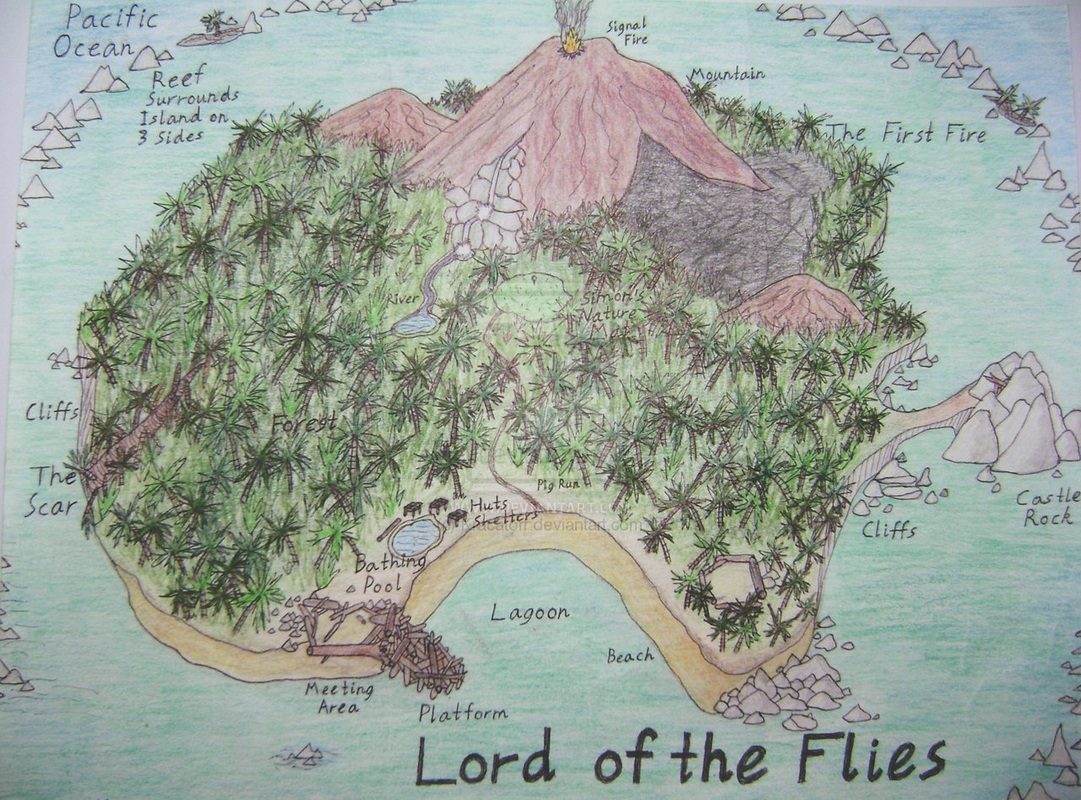

Here’s a nice map of the island I found.

Nicely written, my friend!

Eli Pickering 512-586-7304

>

Thanks for the write-up, Jeffrey, and for the map. Very helpful. A quick search turned up a few interesting variants of the map, too:

Symbolic:

Realistic:

Interpretive:

And my favorite:

Matt