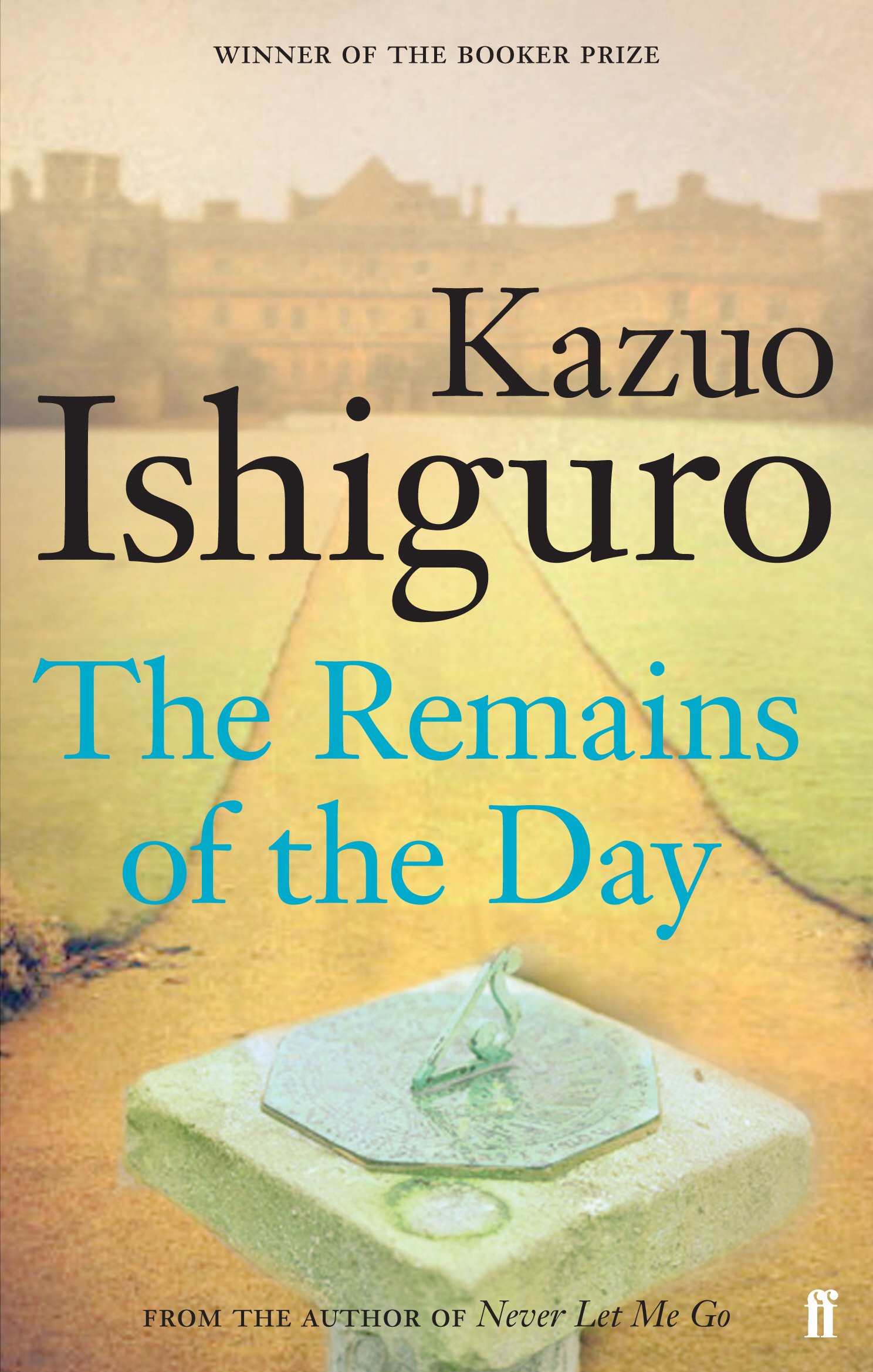

Kazuo Ishiguro is not yet a household name in America, although he is getting close. If you do not recognize his name, you will probably recognize the film Remains of the Day and you may have seen the books Never Let Me Go and The Buried Giant. You may also want to make a mental note that he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2017.

Kazuo Ishiguro is not yet a household name in America, although he is getting close. If you do not recognize his name, you will probably recognize the film Remains of the Day and you may have seen the books Never Let Me Go and The Buried Giant. You may also want to make a mental note that he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2017.

After reading Remains of the Day at Athenaeum, I can see why he was deemed worthy of the prize. His subtlety and his ability to create such a delightful character as Mr. Stevens shows he has a great talent. Our group was enthusiastically thankful and praised the book, the only exception being that some found the book to drag at points. I attribute this to uncertainty in the opening pages about what Ishiguro was doing: why are we reading this long description filled with the arcana of British butler culture, the Hayes Society which admits “only the very first rank” butlers in the United Kingdom, and the names and estates of the handful of truly renown and magisterial butlers?

But like Victor Hugo’s descriptions of Paris sewers and gamin, and Melville’s extended detours into cetology and whale blubber, yet on a much smaller scale, Ishiguro’s few pages on butler culture is actually pertinent, delightful, and in reality a brief background segment of the novel.

Mr. Stevens, our narrator and butler at Darlington Hall in Oxfordshire, was immediately acknowledged to be self-deceived. But the turbulent primary topic of discussion regarded Stevens’ actual character: was he noble? flawed? Was he culpable, or innocent?

When Lord Darlington, under a temporary anti-Semitic influence of pre-WWII German ambassadors, told Stevens he must dismiss a couple of Jewish maidservants, Stevens obeyed immediately and impassively, as if he were ironing the morning paper, despite Miss Kenton (the head housekeeper)’s angry protestations. His defense was the inviolable code of butlery by which he, in maintaining the strictest dignity, is duty-bound is to obey the master with complete and unflinching agnosticism. To raise the slightest eyebrow toward master was grounds for summary dismissal from the Hayes Society, to live out one’s days in bitter opprobrium.

But we all in hindsight question those Nazi soldiers who after the war claimed they were just obeying orders, and we condemn them. Should Mr. Stevens suffer the same judgment of future generations for maintaining his professional standards in carrying out a racist command, indeed one that meant the destitution and unemployability of the two young ladies involved?

All at our table agreed that Stevens failed at that moment; none would countenance the idea that even the lofty dignitaries of British aristocratic society were immune from accountability by one such as Stevens.

The real nut of the question was, Did Stevens ever experience regret for his failure to speak up? A close reading shows that, indeed, three pages from the end of the book, Stevens expresses regret over his complicity in the matter. And the details of context, and the situation of the day, lead many of us to grant some understanding to Stevens.

But was he noble? Can one be noble and amoral at the same time?

Stevens is chlidlike in his awareness of what was going on.

The closest examination of all the facts, which is what we gave it, yielded no  consensus. Each opinion seemed to reflect each person’s unique and complex ethical configuration. More credit to the author.

consensus. Each opinion seemed to reflect each person’s unique and complex ethical configuration. More credit to the author.

Finally, I cannot end this brief summary without admiring the portrayal of the unrealized love affair between Mr. Stevens and Miss Kenton—so sweet, so humorous, and in the end so melancholy. But it could never be otherwise; Stevens’ high ambition to be considered “a truly great butler” drove him to reject and ignore Miss Kenton’s advances, to obey his master’s sinister whims, and to deny himself, until very late and under the administration of his new master, the American Mr. Farraday, a life and interests of his own.

Should Stevens be considered A Great Butler? Would he be admitted into the Hayes Society? Who can say. But Ishiguro has been admitted into the prestigious society of Nobel laureates, and to that I say, here here.